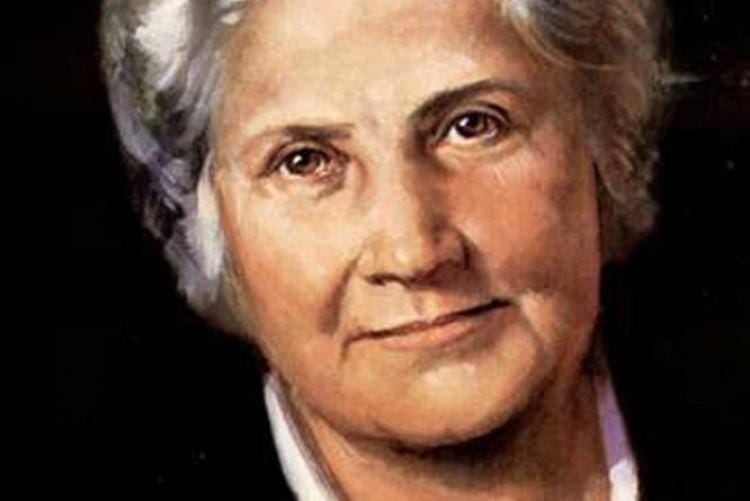

The Fourth Tool: The Insights of Maria Montessori

Usually thought of as the founder of an education system, Maria Montessori also pioneered a reverent approach to catechesis for children

Most people have heard about Maria Montessori as a result of her educational methods and the resulting Montessori schools for children. I attended one as a child for three years until kindergarten, as did all my siblings. As I result of those years, I learned to read quite well before kindergarten, and I remember arguing with my Catholic school kindergarten teacher when she told me I couldn’t read because she hadn’t taught me reading yet.

From time to time as I grew, I would revisit the Montessori classroom where my youngest siblings attended, looking over the materials, re-living that early wonderland of education. But it wasn’t until I married and had children of my own that I began seriously trying to find out what the Montessori method was and who this woman was that I discovered something about Maria Montessori that is nearly entirely overlooked today, even by her most fervent followers.

She was Catholic.

Her life demonstrates the power of one choice—a choice for life—for changing the world. Maria Montessori was a brilliant Italian woman, the first woman to graduate from an Italian medical school. She and a fellow doctor had an affair. Single motherhood was stigmatized in Italian society. Her career would have been over. She could have easily aborted the child and continued the narrative of a feminist path to greatness. She could have abandoned the child, especially when her lover left her for an advantageous marriage.

She gave birth to the child. That choice was life-giving, and life-changing. Sacrificially, she had the child raised by a farming couple and visited him every week to spend time with him and teach him. She turned away from the shining medical career she had been pursuing and began to teach mentally-handicapped children among the poorest of the poor. There, through observation and careful, humanized experiments, she learned that these “idiot children” could learn. She meticulously documented how they learned and began to teach other children in the same manner.

One pivotal day, when her own son Mario was a teenager, he looked across the table at the woman he had been told was his cousin and said, “You are my mother.” She told him the truth and he took her hand and left with her. From that time on, they were always together. He joined her in this work, which became international and changed the education of children forever.

Montessori took some common sense principles into her classrooms: students were put into mixed-age groups, from 3 to 6 years old or from 6 to 12 years old, so the older ones could model and teach the younger ones, as happens naturally in a family. She also focused much on teaching children to be independent: so children in a Montessori classroom might do everything from sweeping floors to cooking lunch for the class or cleaning the bathrooms. She saw the connection between a child putting a material back on its tray and returning it neatly to its proper place on the shelf and learning to read or add sums accurately. Her method is very incarnational as opposed to the abstractions of other methods.

She also saw a consistent value in working with one’s hands. When teenagers are in the throes of puberty, she recommended they learn to work on a farm or fix a fax machine and return to books only when their minds had settled a bit. She also pointed out that any education for humanity must teach children, especially older children, how to grow their own food and care for livestock, which makes them aware not only of the cycles of nature but also connects them to humans throughout history who have had to do the same. As she traveled from country to country and continent to continent, Montessori sought out what unites human beings in their development.

When American educators like John Dewey saw the human child as a blank slate they could mold into the image of the society they wanted, Maria Montessori stubbornly insisted that the child had a soul given by God and a choice to do good or evil. Her anthropology of the human person produces a correct view of education: accommodating fallenness, respecting free will, molding character, forming the imagination of the smallest children with order and beauty and opening them to the experience of God through liturgy and prayer.

Yes, Maria Montessori taught prayer. Asked by the Pope to create a program for teaching the faith to children, she began what became the Atrium program, otherwise known as the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd. It is not so much a doctrinal program as a program that teaches children up to the age of six to pray and to wonder.

Following the Good Shepherd

The key lesson in this program is the Good Shepherd material. The child of three to six years old is introduced first to the parable of the Good Shepherd, not to be confused with the more popular parable of the Lost Sheep. It is instead a selection of the words of Christ in John’s Gospel, chapter 10, beautifully transcribed in a small book and read aloud with great reverence by the catechist to the listening child. The catechist moves small cutouts of a shepherd and sheep on a flat green-painted pasture board bordered with a fence.

The Good Shepherd calls his own sheep by name and leads them out.

When He has brought out all his own,

He goes ahead of them,

and the sheep follow Him

because they know His voice.

They will not follow a stranger,

but they will run from him

because they do not know the voice of strangersI am the Good Shepherd.

I know My sheep,

And my sheep know Me...I am the Good Shepherd. I know My own

and My own know Me,

just as the Father knows Me

and I know the Father.

And I lay down My life for the sheep.

The children become familiar with this work over the three years of the program, learning to move the figures themselves and even memorize the reading. Although they are told the Good Shepherd is Jesus, it gradually dawns on them that they are the sheep and they must learn to hear the voice of the Good Shepherd. The fence represents the Church and within her rules and boundaries is proximity to Christ, the beloved Shepherd.

The children also learn to set a tiny altar with replicas of the vessels and tiny candlesticks, learning the names of each object, and after setting the altar, the candles are lit and they are allowed to sit quietly before it, an activity that small children find infinitely absorbing.

Following the liturgical year exactly, they are read the stories of the great feasts of the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, and Passion of Our Lord and move small figures through these scenes. The great work of the Cenacle, the Last Supper, is done with reverence during the week before the Triduum where the figure of Christ sits at a table spread with altar cloth, bread, chalice, and candlesticks. The story of the Institution of the Eucharist is read. The child can see the connection immediately since the table of the Last Supper is visually nearly identical to the altar material they have already memorized.

But it is only in the third year of the program that the Good Shepherd material is offered again, but this time instead of sheep gathered around the Shepherd, the sheep are gathered around the same Last Supper altar. A miniature Good Shepherd figure is placed on the altar, and then removed, to show only the Eucharist in His place. The sheep are replaced one by one with figures of people, adults and children and lastly a priest. For even priests are followers of Christ.

This slow and precise program builds up the strands of Catholic theology visually in a way for the smallest children that no other program, no matter how traditional quite does. Despite accusations that Maria Montessori was on the liberal side of Catholicism (she died in 1952 but she probably was), that her methods are Pelagian (not true) or flaky (really?), there is a liturgical solidity to the preschool program that can match the Baltimore Catechism. Traditional catechesis in Catholicism begins with the age of reason, and usually all Catholic children do in Catholic preschool is color and learn prayers. (CGS does all this and more, including teaching the parts of the Mass.)

This part of Maria Montessori’s life is nearly completely unknown. The extensive Wikipedia page on her life only mentions the Italian version of her book The Child and the Church, and there is no Wikipedia page for the Catechesis at all, despite there being thousands of Atrium programs reaching over 65 countries. There has been a tug-of-war over Montessori’s legacy for decades and attempts to erase her pro-life beliefs. Yet the Catechesis continues to work its small quiet way in the Church. Its promoters include Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, and John Paul II.

Maria Montessori passed away in 1952 before completing the Catechesis, and her work on the other planes of development was taken over by Scripture scholar Sofia Cavaletti and Gianna Gobbi. Catholic Montessorians argue to this day about how the program changed in its transfer, but the basic bones are there. Speaking of the planes of development, here is another major Montessori teaching.

The Planes of Development

Again, I’m sketching broadly, but the planes of human development discovered and plotted by Maria Montessori have been affirmed by modern research on brain development. Interestingly enough, they also plot fairly well upon the guidelines for classical education as articulated by another great Christian educational thinker, Dorothy Sayers. Interestingly enough, the planes of development echo what has been taught by the Roman Catholic Church regarding the age of reason and the growth in vocation.

I currently teach at a school which is neither Montessori nor classical, but I still use these tools to great effect in my teaching. I could explain each stage (I love doing this!) but in the interest of not making this post much longer, I’ve thought it best to simply post the handout I made for training teachers at our school. I teach high school, so I’ve always been most interested in the third plane of development but it’s worth understanding all three.

What does this have to do with Culture Recovery?

I believe that this information is nearly self-explanatory if you are a parent, because it not only affects how you teach if you are homeschooling but helps you better learn how to understand and motivate your children at any age.

Montessori schools sometimes in their eagerness to spread Montessori ideals give bad advice to parents on how to run their homes. For instance, they might recommend no discipline at all, or fostering an independence without responsibility, or put overly rigorous rules on the parents regarding how to behave in the school. My sister-in-law who founded her own Montessori school used to term these folks “Montessori Nazis.” But it’s good to recall that Montessori was an educator, not a teacher of parents, and as a parent I have found her most commonsense principles affirmed my own instincts.

For instance, she would assure parents that young children are naturally seeking what their parents want them to have. For instance, a baby in the womb can fall asleep on its own, and wants to learn how to continue to do it when it’s born. Since my first baby seemed, to my weary eyes, determined to stay awake no matter what I did, this was a revelation to me. It became a matter of figuring how how he had slept in the womb and accommodating him so that he could learn to do it again.

I’m sure from the outside, my struggle might have looked the same as if I had been forcing him get on a sleep schedule, but the difference was inside me. In an age of single children, where often parents have little experience of parenting until they have children of their own, anxiety is endemic, and the reassurance of Montessori was helpful to me.

Another thing I learned from Montessori was to patiently watch the child and if they were trying to do something—stand up as a toddler, tie a shoe as an older child, open a jar lid—the correct stance was to not help them, not talk to them unless it was necessary, but just watch them. Not their faces, just focusing my attention on what their attention was focused on. Doing that was a good way to love them, to underline that what they were doing was important and necessary and even their struggle was important.

Certainly, I’ve joked that much of the Montessori method with children “comes out in the wash” — in the end, if you love God, your spouse and your children and are striving to grow in virtue with a certain degree of cheerfulness, the parenting method you pick doesn’t really matter. But reading Montessori and absorbing her method of patient observance of the child—not intervening, just watching them work away at learning—was certainly the most revolutionary thing for me as a parent.

In the larger realm of building culture, starting an Atrium is a wonderful way to build up your local community or parish and pass on the elements of culture that are in danger of being lost. Both a sister and a sister-in-law of mine have founded classical schools with Montessori foundations, both of which have borne much fruit. I love how each of them—separately from me!—discerned what so many Montessori Nazis and Classical Purists haven’t yet picked up: that the Montessori and Classical methods of education meld together quite well, which to me is yet another sign of Montessori’s consistency with traditional Catholic teaching.

Most of my children have never been able to attend a Montessori school as I had, but I took the training to become a Catechist in the CGS program, and for many years I’ve been a materials maker, molding statues or painting figurines for the several programs that exist in our area. Most recently, I was able to paint a replica of our parish’s stained glass window for one of the final lessons in the Good Shepherd sequence, where the figures of the congregation and priest and Eucharistic elements are finally placed into the Cenacle, which is transformed to look like the child’s local parish church. Thus the child learns that the way we remain close to the Good Shepherd is by attending Mass as often as possible. It is there that we meet the Good Shepherd, and hear His voice, and know and are known by Him.

My wife and I recently moved to a parish teaching Catechesis of the Good Shepherd. When friends walked us through the classrooms, we were astonished. I've had a variety of experiences teaching homeschoolers and religious ed, but never had I seen anything like this. It was just a few months ago that our friends gave us the tour, and here you are giving contexts. Very timely for me.

And very informative about Maria Montessori. What genius to come through her child's birth and upbringing bearing gifts like this! And what a gift to her - that unexpected love child!

Also, I like very much your chart of planes of development, relating Montessori and her successors with stages of classical education (Dorothy Sayers) and gifts of the Holy Ghost.

And I like your relaxed way of inviting moms and dads to integrate Montessori's insights in their own child raising without sweating the small stuff; i.e., without putting "the system" ahead of their children. Montessori Nazis, eh?

In a nutshell, what's not to like here? Wow, Regina. Thank you for this.