The Fifth Tool: Opus Dei and the way of discipleship

One way or another, we need to be formed and challenged in our relationship with God

I want to share here a difficulty I’ve had for most of my Catholic life: I have been so grateful for the excellent formation in Christ I received, and at the same time have felt helpless to offer that formation to anyone else I know, including my own children.

My formation began in my family as my parents became involved in the charismatic renewal in the Catholic Church, and I was blessed that as their oldest child, I was a witness to much of that movement. Some of my earliest memories are of being immersed in an echoing, reverberating sea of praise in the midst of people in a stadium, hall, or church basement all lifting their voices in song to Christ. Others who encounter the charismatic movement when they were older have felt weirded out or nervous: I was young enough to experience it as peaceful and adventurous at the same time.

There were roughly two streams to that renewal: one that mapped on to the liberal movement of the Catholic Church and remained basically experiential and flowed into and reinforced the various liberal movements and institutions, and another stream that flowed towards reverence and orthodoxy and manifested itself in the lay covenant communities which became the backbone of many orthodox revival movements in the Church. My parents were part of the second stream, and their involvement in the Renewal moved from merely experiencing God to following Christ intentionally.

Doing so required formation. Here I struggle for a definition. Formation in Christ means learning not only the doctrines found in the Catechism (there was no CCC during my 1970s childhood), but also how to live. How to pray. How to conduct yourself as a Christian. Learning to put aside selfishness, pride, self-pity, laziness, impurity, to manage anger and jealousy, control one’s appetites for anything pleasurable so it didn’t take over your life, adopt some practices of self-restraint like fasting, exercise, temporary renunciation (ie: giving something up for Lent), engaging in service to others, whether it be family, the parish, or ministry (usually some combination of all three). It also includes discernment of spirits, how to give and receive advice, how to relate properly with others, your dress and deportment, managing finances and material goods, how to speak with and about others (avoiding gossip or excessive curiosity), a certain amount of psychological self-examination, prayers for inner healing, engagement in the liturgical year, how to be a good friend, how to be a good spouse, how to work with children and teens, the practice of praise and thanksgiving to God, how to pray continuously, adopting a rule of life, how to meditate and various methods of prayers such as lectio divina, and so on.

What was particularly helpful was that in addition to learning this all through experience as part of a family, there were times where I sat down with others in groups and had it spelled out and broken down in a direct teaching, so I didn’t just absorb it (as many Catholics do) but intellectually had to think it through and accept it. More than just picking it up from my home or church environment (Montessori’s absorbent mind stage), I listened as a young teen and adult to “teachings” on so many of these topics, each one relevant to the stage of life I was in, and was afterwards invited to reflect on my own or discuss in a small group in order to bring the teaching into my own life in some way.

This and so much more I learned through the lay covenant communities in high school, during summers, and college. All in all I lived in three states with three different communities and received excellent teaching before I reached adulthood. The difficulty was that I had received these teachings from relatively tiny groups of committed Catholics whose way of life was radically different from that of most Catholics. It was intense, perhaps at times too intense. And I realized even at the time it wasn’t replicable for most people.

The lay communities themselves are difficult to explain. Like a good family, the best and healthiest ones did their work invisibly. The only parts that were publicized to the outside world, again, like families, were their failures and dysfunctions. Looking online, the only articles available are negative, from people who had bad experiences—which may be valid!—or who object philosophically to the whole idea of lay community. So let me try to explain a bit.

In the 1970s and 1980s, many adult Christians were led to commit themselves to meeting together regularly, sometimes even living together in the style of Acts 3, in order to seek God. This pattern among Catholics reflected larger sociological movements among others, including non-Catholic, non-Christians, and non-religious people to create intentional community. Again, we mostly hear about the failures: the ones that turned into dangerous cults. The good ones did their work below the public radar, invisibly, and when their usefulness was spent, they died off naturally, much as a family might come to an end when the parents die and the children move away and lose connection with one another, despite the good formation, memories and feelings that remain.

Having experienced the life in three such communities (and having visited or had contact with many more) I have pondered why they arose. There are two possible instigators others have pointed out: one was the Cold War, and the feeling that the end of the world as we know it was at hand. This was true even among secular people. One response to that existential threat was apparently community-building.

Another was the loss of the extended family through the sociological changes of the automobile. The auto was a technology which allowed family members to live much further apart and brought about loneliness especially in single people and young married couples. There were no longer grandparents, aunts, and cousins to hang out with or have low-impact visits with. Many children went to college far from home and took jobs far from where they were raised, and experienced severe loneliness. The spread of divorce compounded the loss of extended family.

Intentional community was a way of rebuilding the extended family. Looking at the people I know who were most eager to commit to a lay community, they were all individuals who had experienced isolation: single college kids, handicapped adults, young families who were estranged from their families of origin, combined with older generous adults who were willing to take the plunge for various reasons: some had adopted many children and knew they couldn’t raise them alone. Others had reached a crisis in their family life and knew they had to do something differently. How did these people find each other and agree to bond? In the communities I was raised in, we said it was the Holy Spirit who led us to each other. That seems to be as plausible explanation as any other.

There were other factors: large amounts of young adults going to college and taking jobs away from home (again, the influence of the automobile) possibly led to many more singles living away from family and experiencing loneliness and the misery caused by promiscuity and hedonism. The young adult groups in the community were populated by nearby colleges and contained an interesting mix of innocent and devout young adults who didn’t want to get drunk, sleep around, or do drugs, and those who already had and by the grace of God, had pulled back. We were refugees and castaways all, and were able to befriend each other and seek God together.

It was an unusual era, one that has passed away largely, for now. I don’t know of anyone forming new lay communities (even the fad for starting religious orders seems to have ended). Some of the lay communities remain, somewhat smaller. Some have transformed into other entities: a few communities organized parishes in dying diocese and function as parishes today. Others have become Third Orders of lay Benedictines, Dominicans, or Franciscans.

How the community functioned, for those who did not live together, was that each subgroup—adult men, adult women, teens, singles—met weekly for small groups, where people did a study on some appropriate topic, prayed together, shared intentions and struggles, and bonded. On one day, usually Sunday, everyone attended their individual church or parish (we had a handful of non-Catholics along for the ride too), and in the afternoon we met for a two-hour “gathering” for praise, prayer, a teaching, testimonies or sharings from individuals, usually followed by a common meal on feast days or just hanging out for a bit. Those were the basics, but there were many other non-required activities: hikes, parties, water rafting, movie nights, game tournaments, whatever someone felt like organizing for the group. These times of recreation had the effect of drawing us all closer together and helped disenfranchised teens and children bond with the rest. Eventually some of the parents began organizing group vacations, which I’ve written about in another post, and those are among some of my best memories.

The communities were adamant that they were not a replacement for church. Occasionally a Protestant would try to join us as their church, and we had to gently tell them that’s not what we were. Other Protestant churches didn’t quite know what to do with us. The institutional part of the Catholic Church was leery about “religious acting like laity and laity who acted like religious,” and there were years of figuring out the relationship, which erupted into hostility only briefly. Once the Church understood that this work of the Holy Spirit was functioning like a Third Order, some tensions relaxed.

Any group must resist the temptation to be dominated by strong personalities, to become unnecessarily controlling, or to become apocalyptic. We recognized eventually that our job was to just do the boring part: working on growing in virtue, being faithful to prayer, and serving one another. This was what kept the best communities in the background. Few people in our area or in nearby parishes had any idea we were there.

Now, there was always a dynamic tension in the community between certain elements. It was difficult to manage the natural hierarchy of parents over children combined with parents who were to some extent obedient to an outside authority: their community leader, their share group, their mentor. Since we were all fallen adults, mistakes were certainly made. Sometimes parents were too accommodating to the wishes of the community, and the children saw this and were resentful of the outside interference in the family. This especially became true as children became teenagers.

The purpose of adolescence—that interior and questioning phase—is to come to understand yourself from the outside, and how your family and environment has shaped you. You may discover you are angry—rightly or wrongly—over how you were raised or the failures of your parents. No parent is perfect outside of the Holy Family, and neither can every environment be perfect for each person. Anger is the proper response to injustice, and children are very sensitive to fairness. If children are not allowed to voice their feelings that something was not fair, resentment can simmer. Parents can help diffuse this by listening to their child’s feelings and helping them to evaluate them, but the confrontation of the child with his or her past must to some extent be worked through alone. The result should be a combination of gratitude and strategy; gratitude for the undeserved good they have received, and strategy to deal with the shortcomings of their upbringing. Perhaps a parent died, leaving a wound. How can we find healing for that wound? Perhaps you have a scrupulous or sensitive temperament: how can you become more forgiving of yourself and others? Perhaps you are tough and insensitive: how can you learn more charity and openness?

A teenager raised in the community not only had to deal with this universal parental/familial struggle but also with the additional layer of community. Some teens and parents negotiated this well. Many, unsurprisingly, did not, especially in the first generation of community where everyone was just trying to figure things out.

So it was not surprising that the majority of grown children raised in communities, whether they were grateful or resentful of that fact, opted not to raise their own families in community but they used the formation they had received to raise their own children and conduct themselves in their parishes. This pretty much describes my husband and I, who live far from any lay community and have opted to do our part in building community in our parish instead.

Now the communities that remain are in the third generation, but times have changed, and often the grown children who have left the community don’t fly far from the nest but instead settle in the same town or nearby. They may attend some community events without becoming members, in a way reminiscent of how in the Middle Ages, people settled in farms or villages outside of monastic towns. (Incidentally, this sort of loose community building still happens around thriving religious orders today, especially among the traditional orders, as well as around the handful of faithful Catholic colleges—which explains the parish I currently attend near Christendom College.)

And despite being as low-profile as hobbits in Middle Earth, the lay communities have inspired and supported fruitful and dynamic ministries. Some of the small and large works which have come forth as a result of or were heavily supported by lay communities include Renewal Ministries, Heart of the Father’s Unbound deliverance ministry, Servant Books, St. Paul’s Outreach, Sisters of Jesus Our Hope, and Franciscan University.

I have spoken much here about community (and I plan to again) but this post is about formation in Christ, which in my case was provided by these communities. I so much value that formation and the problem I had was how to receive it and pass it on outside of that environment.

Fortunately, Our Lord has provided another tool, and that tool is Opus Dei, the movement founded by St. Josemaria Escriva. Opus Dei, the work of God, is probably the most “secretive” movement in the Church today, and hence much misunderstood. Even I probably don’t understand it completely, but here is my experience.

I have spent my life in Catholic professional circles and I have met and worked with many, many Catholics. We professional Catholics are a mixed bag, like Catholics in general. Hypocrisy is our constant temptation since our devotion (or appearance of devotion) is kind of what provides our paycheck, and there’s a besetting temptation to skimp on your relationship with God because “God is what you do all day.” I imagine priests must often feel the same way. When religion and business mix in apostolic work, it can be dicey. Sometimes people assume that their personal devotion to Christ will compensate for a lack of ethics or professionalism elsewhere. I got used to lowering my expectations for my fellow Catholics in business accordingly. But every once in a while I would meet a Catholic who seemed genuinely consider that their relationship with Christ meant they actually had to behave in a Christ-like manner. There would be a situation in which tempers flared: but that person would act as a true peacemaker, with humility, often being the first to apologize or offer to make amends. Or they simply paid their invoices on time, were always pleasant to interact with, or went the extra mile to ensure that their product or service was good. Or they were someone I knew personally who had a genuine concern for the faith, but not in a political or ostentatious way, who neither displayed nor hid their devotion to Christ, but who acted as a decent, generous, cheerful and kind person. When I remarked on this to someone else, they inevitably responded, “Oh, him? (or her?) They’re Opus Dei.” After this happened for the fifth time to me over the course of ten years, I said, “Ok, where do I sign up? Because this is the sort of Catholic I want to be.”

Fortunately the person who I said this to said, “Well, I’m a co-operator, so I can help you out.” I say fortunate because unless you know the password, so to speak, it can be difficult to get into Opus Dei. Their founder, St. Josemaria Escriva, was more than usually determined to downplay their apostolate because he kept insisting that the important thing was that people encounter Christ, not Opus Dei. So if I had never asked directly how I could join, I might never have found out more.

Opus Dei doesn’t have assassin albino monks (darn!) or secret decoder rings, but they are elusive. Members are asked to come up with some apostolic work they can engage in, whether it’s helping at a soup kitchen, volunteering to teach religion, or simply engaging in the apostolate of friendship with their non-religious friends or co-workers. But if they do something more formal, they are not allowed to indicate it’s in any way connected to Opus Dei. Nor in general should they proselytize others into the movement. Everything is to be done for Christ and for others.

In doing so, they remind me very much of the fictional Spies of God imagined by Myles Connolly’s hero in the 1928 Catholic classic Mr. Blue (also known as the best book Chesterton never wrote):

Blue was confident that in this work lay his career. He hoped, he said, that others would some day join him, others who would go into the factories and great offices and teach, as comrades there, by character and example. They would be the Spies of God, he decided. Their unselfishness, their patience, their courage, their amiability, their fine wholesome lives would be living sermons to those who read only the newspapers and disdain the preacher. He even hoped that someday his spies would go into crafts like journalism and advertising and try to win men to a desire for the truth and an affection for beauty. And such, briefly, was his great dream of a Secret Service for God.

When I read of Escriva’s plan for Opus Dei, it reminds me very much of a surprising incarnation of Connolly’s fictional vision. Like Blue, Escriva envisioned Catholics going into the world and evangelizing simply by becoming good at what we do out of love for God and to make Catholicism attractive to others in doing so. His emphasis on professionalism as an evangelism was groundbreaking for me, pointing out that to be excellent in one’s work can be a way of drawing souls to Christ. A sample of his writings on work:

“For a Catholic work is not just a matter of fulfilling a duty—it is to love, to excel oneself gladly in duty and in sacrifice.”

“Carry out your work in the knowledge that God contemplates it: ‘laborem manuum mearum respexit Deus’ ( Gen 31:42) God regards the work of my hands. Our work therefore has to be holy and worthy of Him: not only finished down to the last detail, but carried out with moral rectitude, nobility, loyalty, justice."

“Then our professional work will not only be upright and holy but will also be prayer as well.”

Escriva’s writings are simple and straightforward, spelling out what should be commonsense, prodding and pushing one to actually grow and change. And yet he had a way with phrases that is making it very difficult for me to pick my favorite Etsy coffee mug or watercolor print to spotlight here. It’s funny but perhaps fitting that there are few statues or icons of Escriva’s laugh-wrinkled face, but that his words can be found all over the Catholic universe emblazoned on the most commonplace objects.

It was through becoming a cooperator in Opus Dei that I discovered a method of formation that did not require constructing a lay community, wonderful as they are, but simply meeting with a mentor, forming a rule of life (prayer and discipline), and following it. Like the lay communities, they offer circles for men and for women according to their state in life. one-on-one mentorship or spiritual direction, confession, and annual retreats. And their retreats and advice much resemble what I received over the years from the lay communities. I’ve never lived close enough to a Opus Dei center to find out if they do fun stuff too like water rafting, but I’m mainly going in order to work on my own soul.

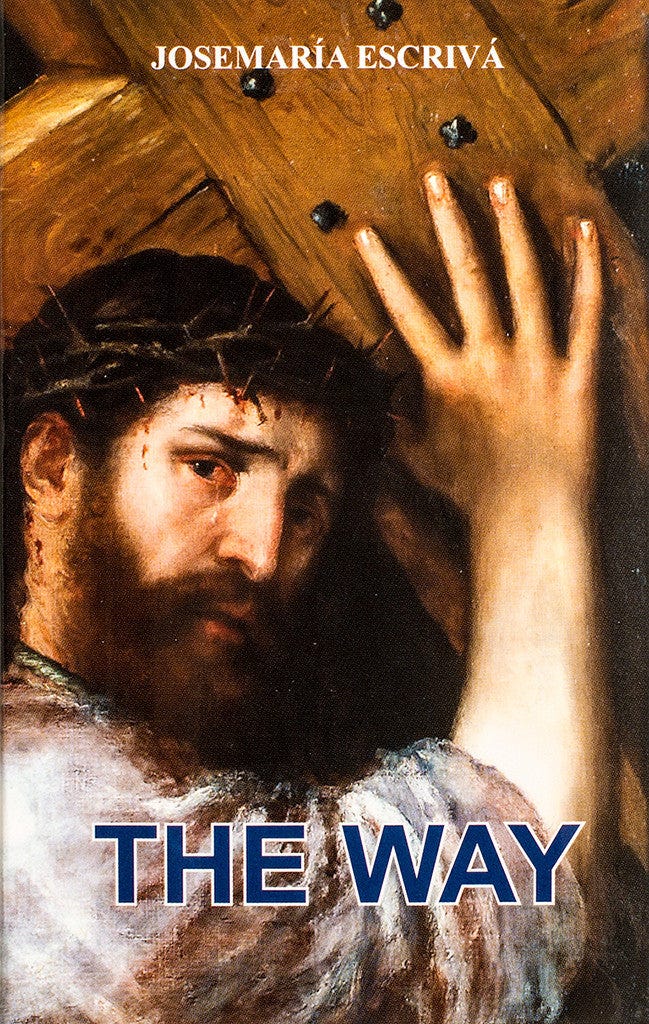

Even without connecting with an Opus Dei circle, one can find inspiration and direction in the little books Escriva wrote for busy people: The Way, Furrow, and Forge. I usually keep one in my bag. They contain bits of good advice that read like tweets. You read until one of them strikes home, and then you reflect on it. Each book is divided into chapters, typically on different virtues. But I was intrigued by the virtues Escriva picked: not only the usual ones, but ones like Courage. Ambition. Daring. “God and daring!” was one of his sayings.

I am focusing on Opus Dei because it does something very different from other Catholic movements that I have seen. Most movements focus on a devotion, a prayer technique, a theology, something intellectual like apologetics or political theory or culture or Church history, or a particular social ministry such as pro-life work or works of mercy. These are all well and good, but Opus Dei’s materials and mission are really just about helping each Catholic become a holier and more virtuous person, and hence it’s fairly boring. But that kind of formation is so crucially lacking nearly everywhere in Catholic life, outside of good families and a few excellent parishes and colleges.

Escriva’s insights into the role of the laity foreshadowed the teaching of Vatican II on the laity, and he added a strong, very masculine element to Therese’s spirituality. His apostolate of friendship—evangelism not as a one-time transfer of information or an experience of emotion but as an ongoing influence of life—is practical and inspirational. Over and over, he provides commonsense Christian virtue, the practicalities of wisdom. Participation in the Work, as it’s called, is to take on the practicals of Christian discipleship.

There are other apostolates that also teach the life of virtue, of course. Many of these are localized (as they should be) but I am focusing on Opus Dei because it is easier to find no matter where you live (you have to know where to look, of course), it is international, and because it is the movement I’m more familiar with. Having been involved with somewhat intense communities, I appreciate the looseness and freedom that Opus Dei has in its structure, which is anti-cultish. The apostolate of friendship is an idea I wish we could all adopt, and I find much in its work that could be emulated and adapted.

Seek them out to learn more. The code word is, “I’d like to find out about becoming a cooperator with Opus Dei.”

Regina, I loved your opening paragraph - your thankfulness for the formation you were given, your helplessness to pass it on. Also, after that, what you wrote about your paths through and in lay communities - lostness in our youths, finding passing homes, friends, Jesus - then moving on into life, adulthood, family. Almost an incubation it was, our prayer-group studies and friendships. Impossible not to miss them, moving on.

But how our helplessness hurts! - When our own children are lost and have little besides the monoculture, social media, other lost children to light their way.

This is a grief. Your story about Opus Dei may be a help. I didn't notice whether Opus Dei folk get together to talk, pray, think. I like what you wrote. It resonates with my own history. And Opus Dei's quiet, trusting ministries certainly fit with my own inclinations.

But how to save what's being lost? Lost children especially. Somehow, I'm left sad here, with merest threads of hope.