Evolution vs. the Silmarillion

Some thoughts on the trajectories of worldviews and how it affects us

This is a post about philosophical assumptions, the foundational maxims we presume to be true and upon which we base our reasoning. I admit this is a bit of a change from the practicalities and household minutiae of Culture Recovery, but nevertheless, even the householder must examine one’s worldviews from time to time. And some years ago, as I began to delve deeply into the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, I discovered just how disjointed some of my own presuppositions could be. This post will be easier to understand if you are somewhat familiar with the works of Tolkien—and I’m not sure how helpful it will be if you are not!

For those of you who are unfamiliar, Tolkien’s masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings, a trilogy consisting of The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. famously made into blockbuster movies nearly 25 years ago, deals with the peril and rescue of Middle Earth, presumed to be our own world in the distant past. What distinguishes Middle Earth from our earth is the presence of immortal elves who build kingdoms and fight back against dark powers. When the elves fade away and leave Middle Earth, the Age of Men (presumably leading to our own age) begins. The Silmarillion is Tolkien’s posthumously published collection of the backstory of Middle Earth, which purports to tell the elven version of history from its beginnings before time up to the Fourth Age, the Third Age being the time in which Sauron’s rings are created and then destroyed, thanks largely to the efforts of the little people, the hobbits.

As I read and re-read The Silmarillion, finding it even more engaging than its more famous precursor, I discovered something about Tolkien’s world, namely that it was quite anti-evolution. I don’t mean that Tolkien claimed that God created the world in six days or that the earth is only six thousand years old—although Tolkien may have assented to that in faith—but that his view of the world was profoundly opposed to the trajectory of evolution itself. Given that evolution is a major component of the worldview of modernity, this discovery was jarring to me.

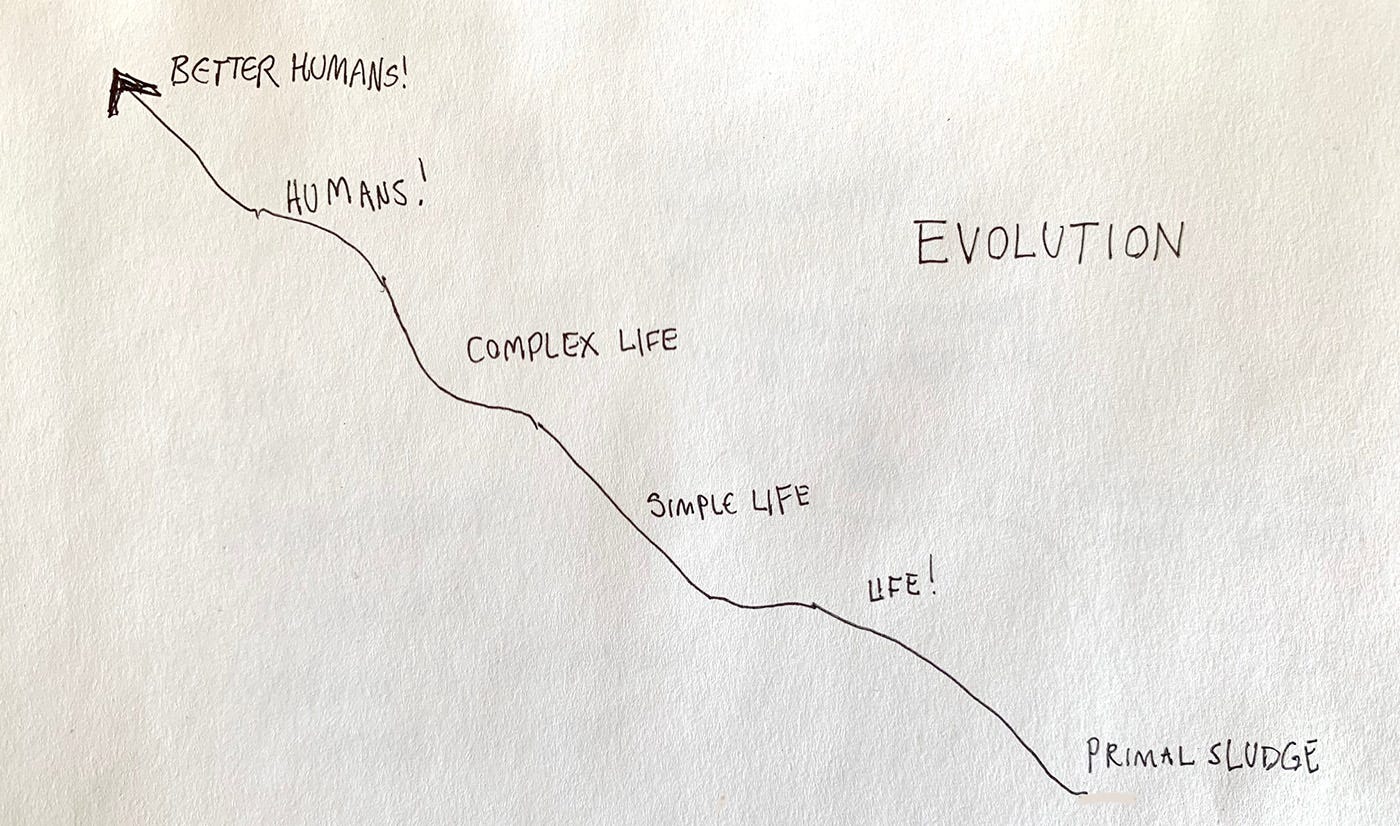

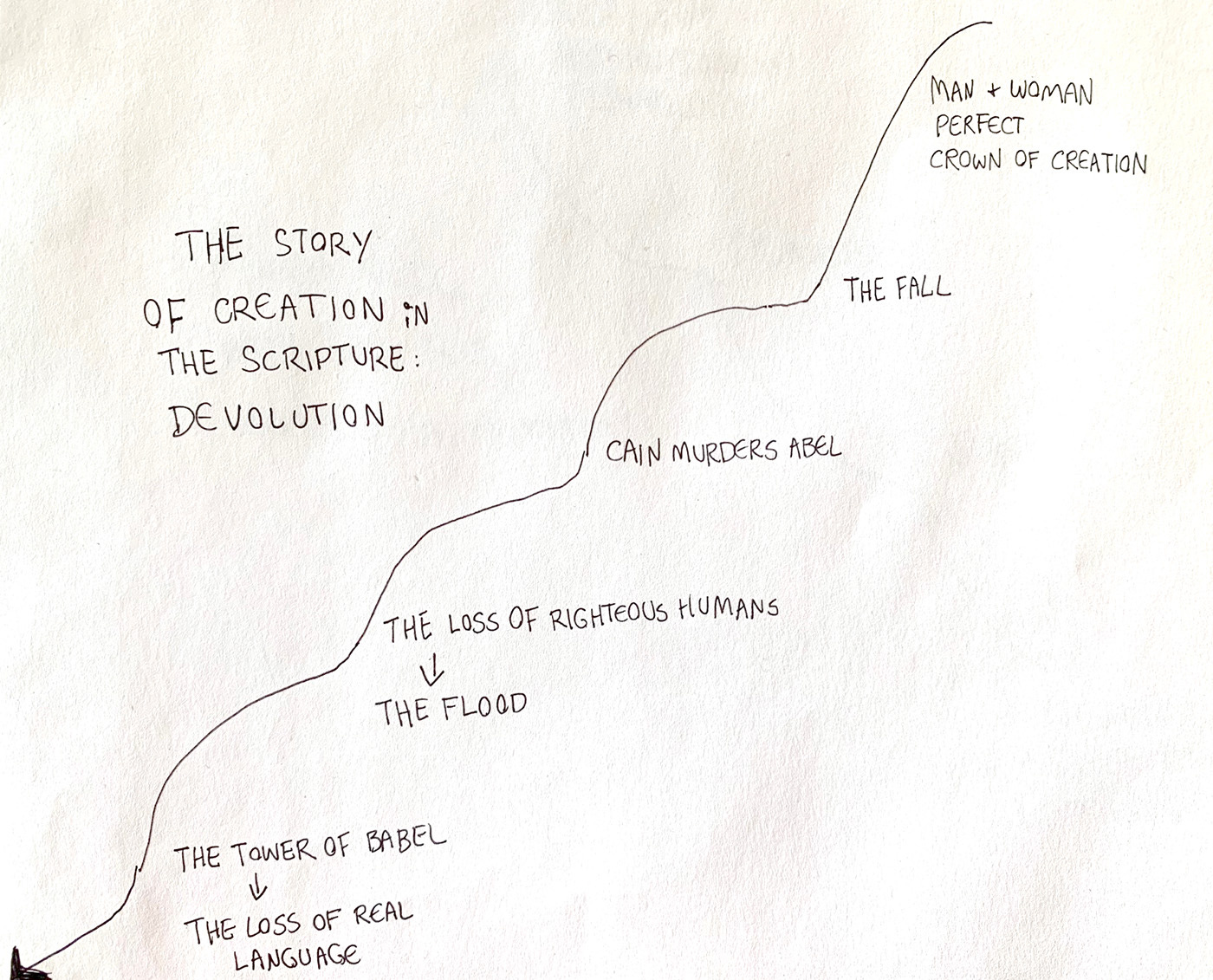

If evolution means anything, it demands an upwards trajectory. From non-living material comes forth simple life—and from that comes forth more and more complex life, eventually producing sentience and consciousness, as you can see from this helpful visual I’ve scribbled.

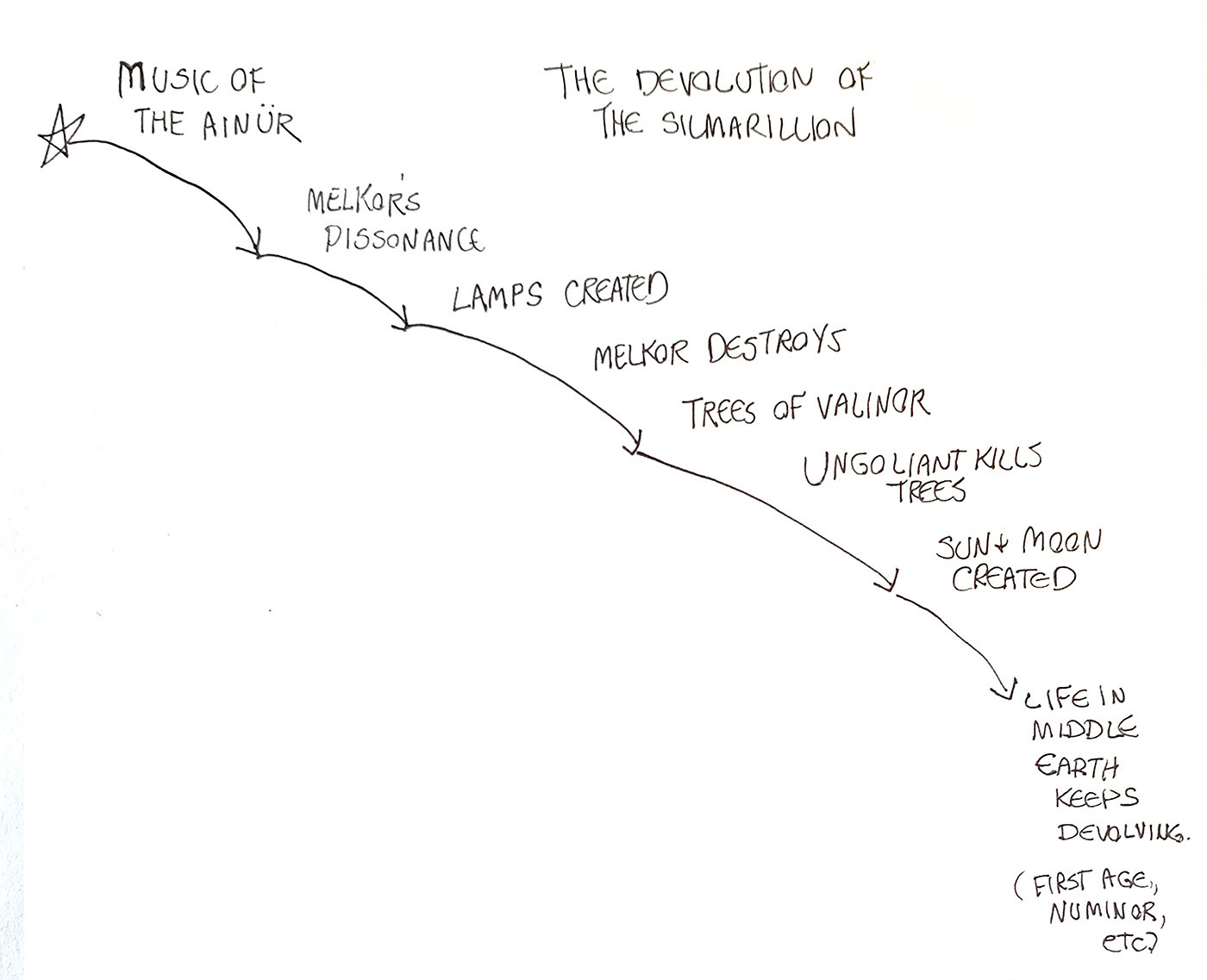

Tolkien’s version of creation is actually a reverse trajectory: Eru, the One (The Biblical God, for all intents and purposes) creates a perfect world, Arda, which is then marred by Melkor. With the help of the Valar, the sub-creating angels of Tolkien, Arda is repaired —only to be marred again by Melkor, who destroys the world’s sources of light, the great Lamps of Arda. The lamps are replaced by two glorious trees, which Melkor, now Morgoth, poisons with the aid of a massive spider, Ungoliant—and in the end the world can only be lit by two fruits from the dead trees, which become the Sun and Moon. Thus our world is a pale result of what God and His emissaries intended—and the future is bleak indeed.

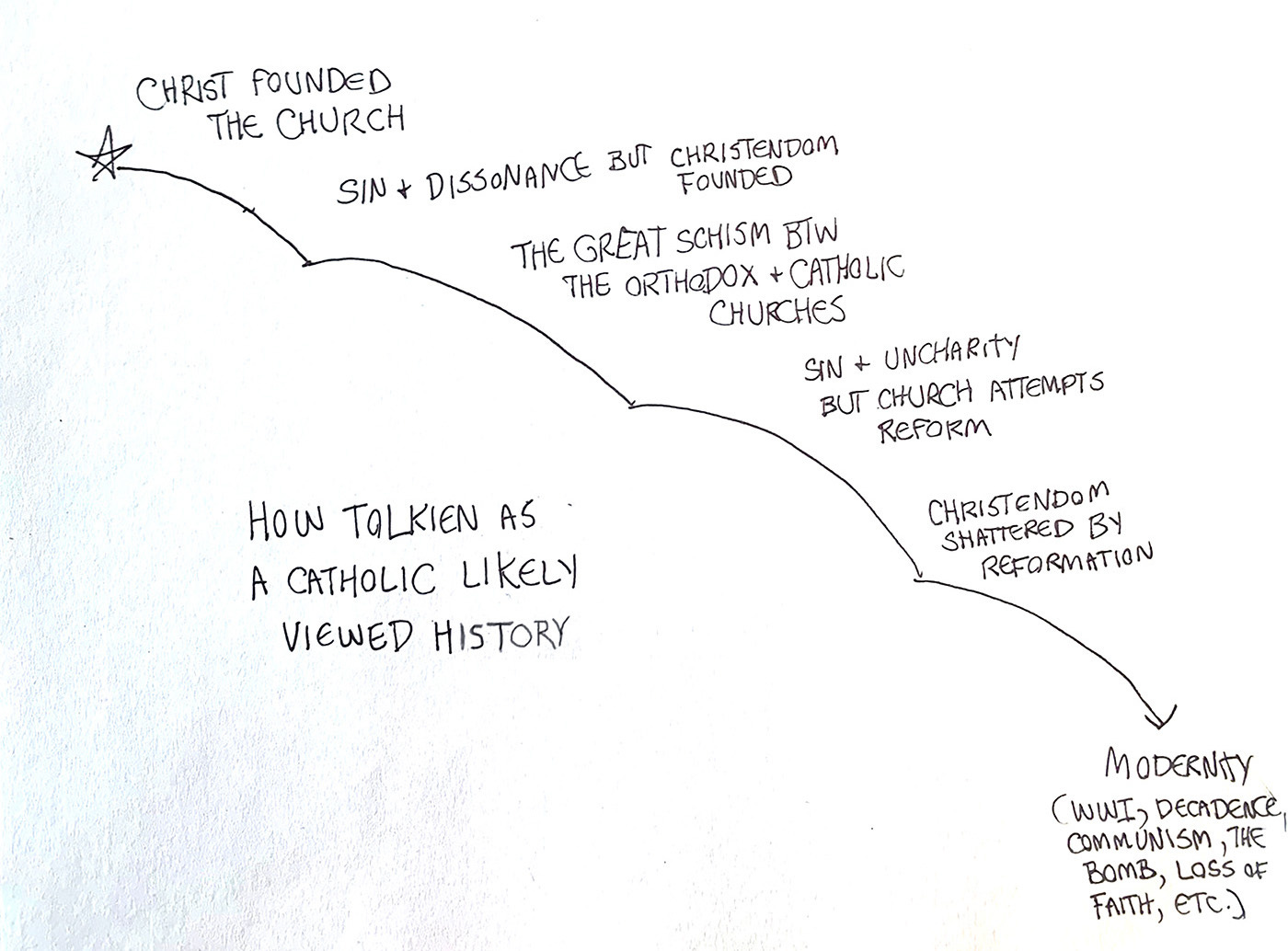

What was unsettling to me was to recognize that Tolkien’s view of the world as devolutionary maps quite neatly onto the view of historical Catholicism, whereas it is out of joint not only with evolution, but also with the viewpoint of Protestantism. As a Catholic, I found myself challenged because as an American in the modern age, so much of my thinking is unconsciously Protestant and hence, evolutionary.

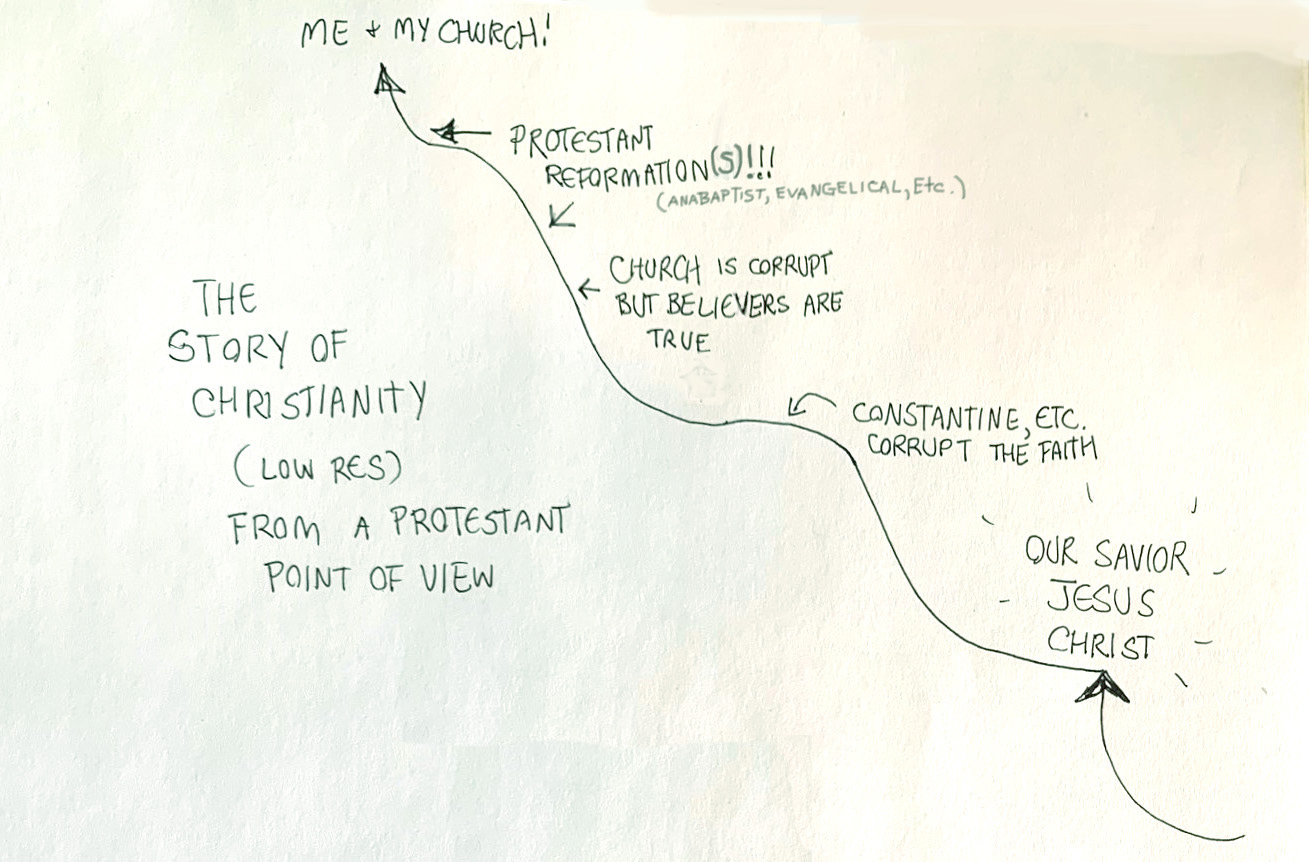

In fact I would argue that the mindset of Protestantism requires a belief in evolution, insofar as it demands an upward trajectory in its perception of history. The following diagram doesn’t pretend to capture all the nuances of Protestant thinking (a good Protestant historian acknowledges complexity) but I believe it captures a sort of vague and unexamined view of history for many American Protestants.

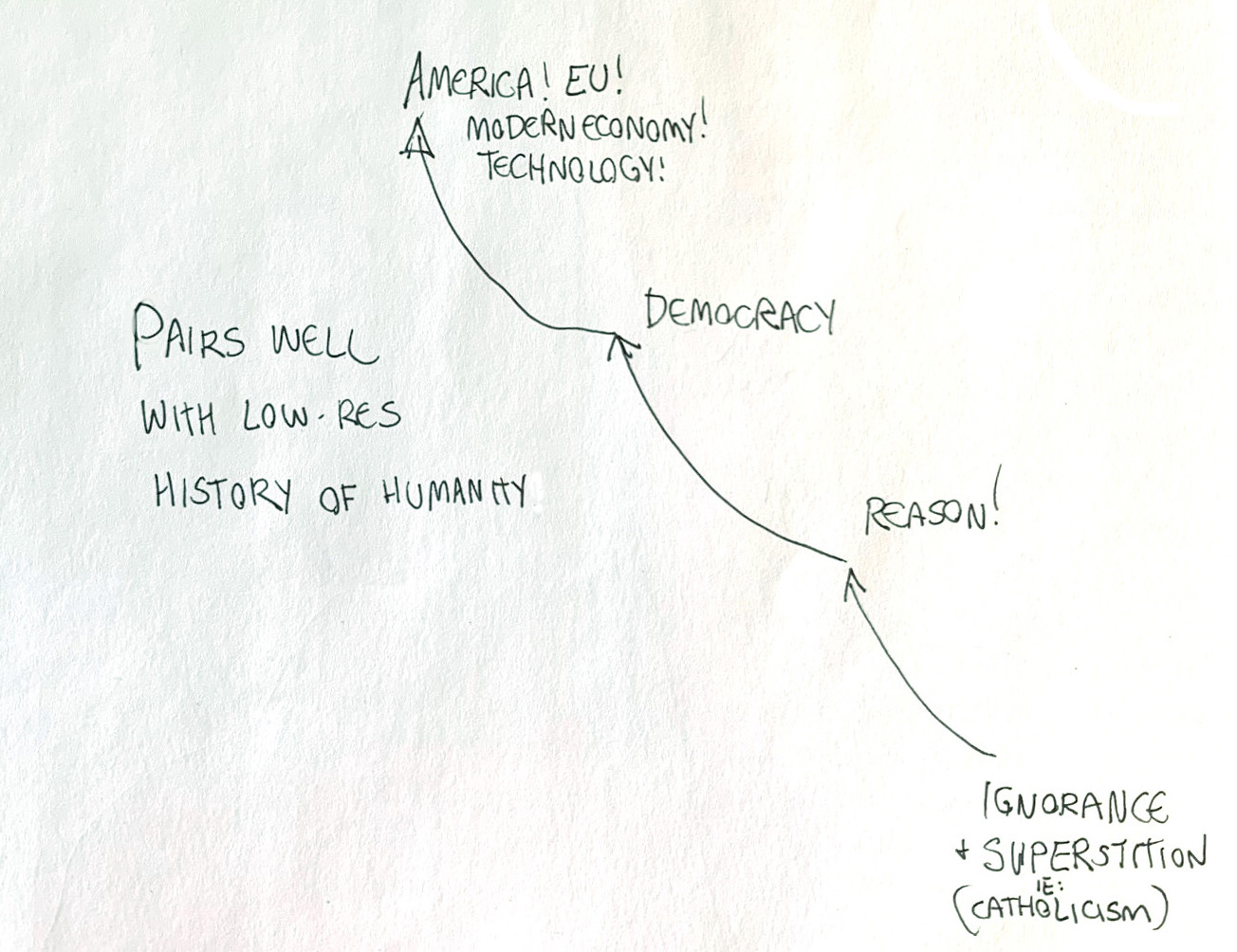

Notice how this upward trajectory not only pairs well with evolution (which is perhaps why the theory of evolution historically had a so much more disturbing effect upon the worldview of Protestants?) but also with the vague and unexamined worldview of history of many Americans.

Now, The Silmarillion does not purport to be an actual account of the history of our world, naturally, but it’s interesting that it actually does map on quite well to the Biblical account of history in the first chapters of Genesis, which is also profoundly devolutionary:

This was interesting to me as a Catholic, and it gave me some insight as to why the Silmarillion felt so truthful despite its fantastic trappings. Of course Tolkien’s creation account also owes much to the Northern myths with their similar bleak outlook on history. But then, I began to consider how The Silmarillion not only mapped well onto the Biblical account of history but also onto how Tolkien as a Catholic might have viewed the history of Western civilization, leading up to his own life in the twentieth century.

This downward trajectory felt uncannily like the account of the falls of the lamps, the trees, and the various elven kingdoms as detailed in the intricate accounts of The Silmarillion. I had already noticed in my readings that the map of Middle Earth in the Third Age bears a faint resemblance to the map of Europe, with the Shire posited roughly where England is, making the key kingdom of Gondor situated about where Rome is today. For Tolkien as a Roman Catholic, Rome and the Vatican would have had the same leadership position as Minas Tirith had for the inhabitants of Middle Earth. I also knew that in Tolkien’s attempted sequel to The Lord of the Rings, Gondor falls into peril once more as the souls of men forget the elves and begin to become fascinated by orcs and Mordor.

It seemed as though Tolkien was consciously or unconsciously telling us how we ought to see the world: a warning that we were on a downward slope that no earthly hope could save us from. Remember, from the viewpoint of a Catholic, the Reformation was no reform but a disaster, heralding the shattering of a unified way of life and the doom of Christendom itself. Tolkien himself, seeing the chaos after the Second Vatican Council at the end of his life, did not see any light at the end of the tunnel for Christian culture. In the same way, the Catholic Church is forced to view her own history as a series of fighting constantly to stay in place, inevitably losing ground even as victories are won in other places. There can be no happy ending so long as life on earth continues, much as the elves are trapped within Arda with no hope until Eru remakes the world. In many ways, the elves with their long life and unbroken history act as a sort of “Church” for the inhabitants of Middle Earth, preserving the tales of the good and the follies of elves, men, and dwarves.

“Don't adventures ever have an end? I suppose not. Someone else always has to carry on on the story.” — Bilbo in The Fellowship of the Ring

Now, you can argue here that Tolkien was not a strict devolutionist, but a Christian—and hence his dismal view of the future was his accurate assessment of the state of mankind (and elvenkind) without Christ. The lesson of the Legendarium is that there is no salvation in elves or hobbits, but that all must do their part regardless in fighting against the darkness.

Hope came to the world first through the revelations to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and ultimately came through Jesus Christ, God-with-Us, Word made Flesh, and splendor of the Father. Tolkien of course believed this. Hence Tolkien’s world makes space for this revelation and never once claims that any of his characters could be the Messiah (unlike other fantasy worlds, such as Dune).

The fascinating paradox at the crux of his masterpiece is that the hero, Frodo, ultimately fails in his quest to destroy Sauron’s Ring and the world is “saved” by his previous act of mercy towards an unredeemable and treacherous villain, Gollum. Thus the salvation of Middle Earth in the Third Age is accomplished despite human frailty by a mysterious mercy, a story which has touched the hearts of atheist and believing readers alike.

The Truth of Fighting the Long Defeat

So if Tolkien’s worldview profoundly contradicts the modern worldview, why does Tolkien’s story have such power in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? I would argue that this is because his devolutionary worldview speaks a powerful truth to the modern reader. Despite all our lip service to progress and evolution and glib assurance of cultural victories because “America is God’s country,” we suspect deep down that all our efforts might make no difference after all: if we are honest with ourselves, there is no earthly victory in sight.

Here The Lord of the Rings does not counsel for us to despair, like his character Lord Denethor, but to continue on, “fighting the long defeat,” as the Lady Galadriel says. It was this very phrase, “the long defeat” that summarizes Tolkien’s worldview. The characters in all his work struggle against the powers of chaos and darkness—Morgoth, Sauron, the orcs—and win some victories. But always, strength turns to weakness, light fades, and the darkness returns again, to be fought back once more.

But Tolkien is not a nihlist: far from it! Once you recognize his profoundly contrarian worldview, you can see his entire creative work, particularly The Lord of the Rings is permeated with advice and counsel and wisdom on what one should do once the truth of devolution is recognized at last. Tolkien urges us implicitly to be like Bard the Bowman of The Hobbit who is a doomsayer and pessimist, but nevertheless is the one person alert to the danger of the dragon when it comes.

“Despair is only for those who see the end beyond all doubt. We do not.” - Gandalf, The Fellowship of the Ring

When the hobbit Frodo realizes that the world of his childhood, the idyllic Shire, has been invaded by agents of Sauron bent on destruction, he regrets that he has been born into such a perilous time.

“I wish it need not have happened in my time," said Frodo.

"So do I," said Gandalf, "and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

The young Tolkien was born into a “evolutionary-worldview” which presumed the world was progressing inexorably towards order and utopia—and that worldview, if he ever held it, was shattered by his experience on the Somme in World War I. Clearly there was something wrong with this idea that things were constantly destined to improve. As he aged, Tolkien grew more and more contrarian in asserting its opposite: darkness would continue to march upon the world. It’s not too surprising that his work resonated with the post-World War II generation, which had been told that their side “won” the war but were facing possible nuclear annihilation.

It’s also not surprising that the Ring of Power continues to represent for readers an unconscious symbol of a fascinating but sinister technology that was known to be lethal and yet was too beautiful and powerful to put aside altogether. This technology can be analogous to AI, or even smartphones (which for many of us act upon us like the Ring of Power—we keep attempting to put them aside but somehow they always end up in our pockets).

Tolkien insists in his famous introduction that The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory of World War II—and makes his case by giving his view of World War II, that the great evil of Sauron was merely contained, that Saruman appeased, and that hobbits were facing contempt and even destruction. In other words, his view of earthly history is profoundly devolutionary. He even says as much in his letters.

“Actually I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ - though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.” - Tolkien, Letter 195

Confronting this view of history lead me to revise my own. I no longer subscribe to the view of either evolution or progress or that there is any sort of positive destiny inevitably marching our way. And there’s a sense of relief in this. If there is to be any sort of victory in our culture wars and culture recovery, it will be because God intervened. But there is a sense in which we need to be obedient to the requirements of our faith, hopeful, tending to our duties and responsibilities, and doing what we’re asked to do as part of our vocation.

“The world is indeed full of peril, and in it there are many dark places; but still there is much that is fair, and though in all lands love is now mingled with grief, it grows perhaps the greater.” The Fellowship of the Ring

And while the Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion are full of heroic characters and grand deeds, adopting its worldview reinforces the truth that even the small characters, the hobbits and children and ordinary people of our own world, have a part to play in fighting the darkness, and yes, recovering and preserving culture.

“Such is of the course of deeds that move the wheels of the world: small hands do them because they must, while the eyes of the great are elsewhere.” — The Fellowship of the Ring

Thus I hope I’ve been able to pull some philosophical threads together to show that the evolutionary mindset can be illusory and self-defeating, whereas the more realistic view of Tolkien as found in Church history and echoes in his imaginative works is ultimately the more helpful and hopeful for the business of those engaged in Culture Recovery. And if that helps to explain why so many people find Tolkien’s works such a lodestar in their lives, so much the better.

I welcome your comments.

"The long defeat" is indeed essential in understanding Tolkien's mythology. And it can be a Debbie Downer POV. But as you note, living in Protestant triumphalism is also problematic.

Tolkien's theory of eucatastrophe ("On Fairy Stories") is the articulation of the literary solution to the dilemma between the two poles, though. It makes the joy of the miraculous turn in every story more sweet for the defeatist, and reminds the triumphalist that true hope lies not in our own actions (which are nonetheless necessary) but in the One really DID triumph over death. There is a redeemer.

"Oh, that my words were written! Oh, that they were inscribed in a book! Oh, that with an iron pen and lead they were engraved in the rock forever! For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at last He will stand upon the earth; And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another. My heart faints within me!"

Those words from Job 19 are Tolkien's vision, written from the point of view and loss and defeat, and yet casting forward toward victory--toward a messiah as yet unseen, just as the denizens of Arda and Middle-earth know nothing of Jesus, who remains far in the future. And yet Jesus is there in the prophecies, and prefigured in Aragorn (Estel, hope) and his return as king as a type of Christ.

Excellent.

Does not Our Blessed Lord gesture towards the same devolution in Luke 18:8: "When the Son of returns, will He find Faith on earth?"